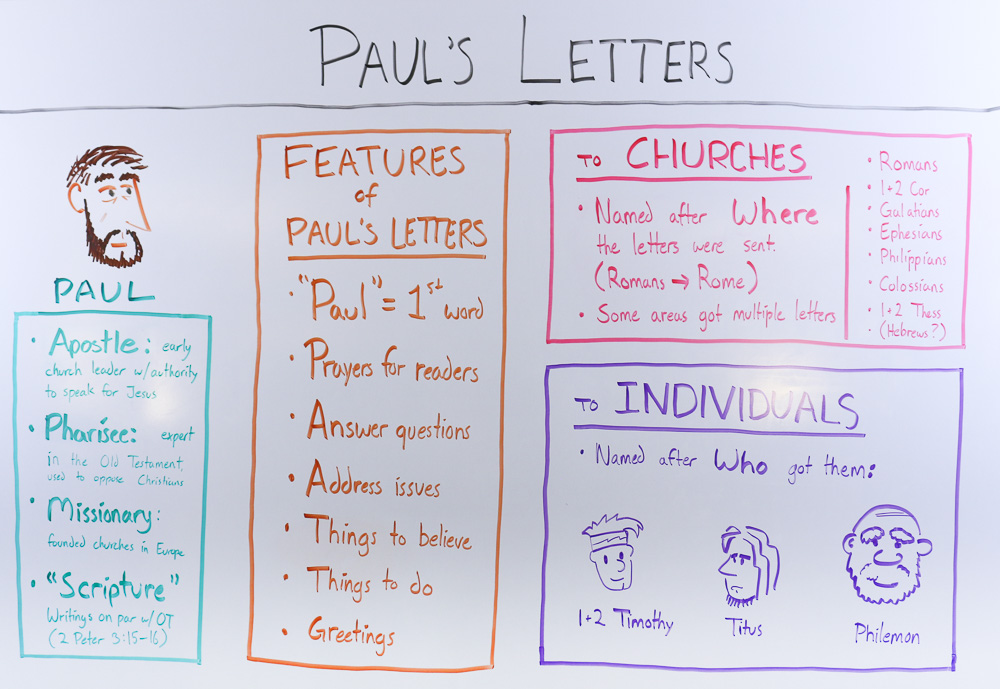

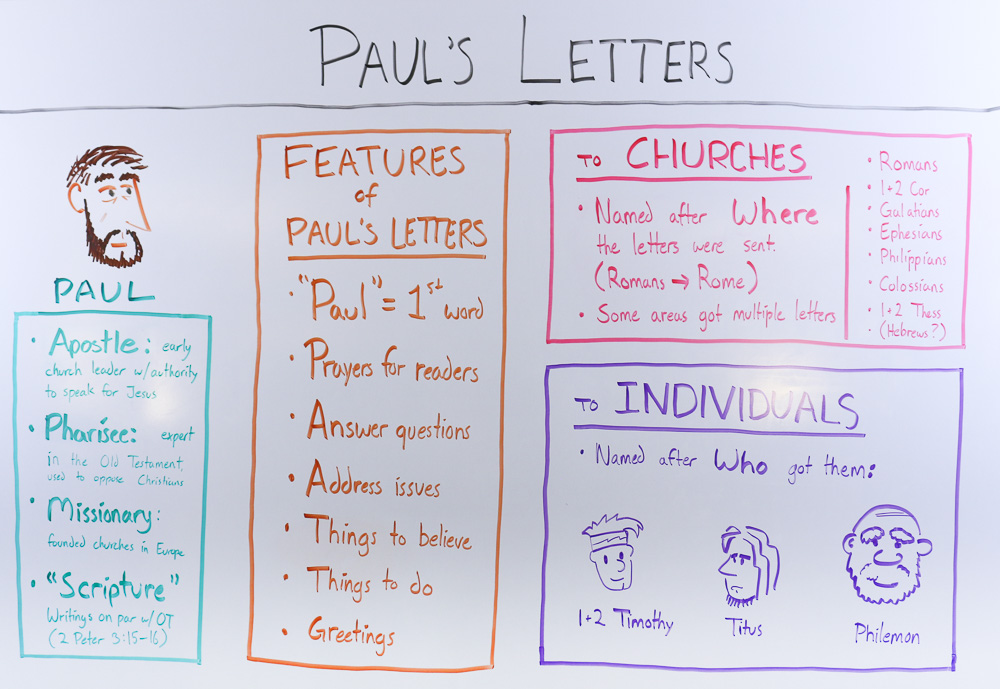

A young man named Saul was bent on eliminating Christianity from the face of the earth. He was a Jew, a Pharisee (well-versed in the Old Testament), a man of knowledge, letters, and spirit.

Then Jesus directly intervened. The risen savior appeared to Saul on the road to Damascus—an encounter that completely transformed him. This man Saul became the beloved apostle, saint, evangelist, theologian, and pastor we call Paul.

Paul’s an important character: out of the 27 books in the New Testament, Paul wrote 13.

Out of all the biblical human authors, Paul has written the most books of the Bible.

Paul was chosen for a few specific tasks (Eph 3:8–9):

We see Paul doing the first in the book of Acts. We see him doing the second in his letters (there’s certainly overlap, though).

Most of Paul’s letters fall into two groups: letters to churches and letters to individuals.

Nine of Paul’s letters were addressed to local churches in certain areas of the Roman empire. On the whole, these epistles tend to deal with three general issues:

Paul’s writings on application are usually rather general. You’ll see Paul telling children to obey parents, masters to be kind to their slaves, and the like; you won’t see Paul giving children a list of things to do, or giving masters a bill of slaves’ rights in the church.

In short, Paul focuses on the “why” (doctrine) and the “what” (application), not the “how.”

Paul’s a very organized writer, and these epistles can usually be split into sections based on these issues. The book of Romans is a good example:

As you read these epistles, keep an eye out for these themes.

Here’s the list of Paul’s epistles to churches:

Three of Paul’s letters are addressed to individual pastors. Two are written to Timothy, and the last is written to Titus. Because these letters are for specific individuals, they include more specific instructions than the other letters.

Paul considers Timothy and Titus to be his sons in the faith (1 Ti 1:2; Tt 1:4). He trusts them to manage their local churches well (1 Ti 3:15; Tt 1:5) and maintain his sound teaching (1 Ti 4:6; Tt 2:1).

Here’s a high-level idea of what each pastoral epistle is about:

Today, these letters still teach us how the church should be managed—they’re especially helpful for church planters.

Philemon is a hybrid of the two categories. It’s a message to Philemon, a leader in the Colossian church, but it’s addressed to the church his house as well (Phlm 2). In a way, it’s an open letter to an individual.

Philemon’s runaway slave had converted to Christianity, and Paul was sending him back to Philemon. Paul encourages Philemon to welcome the runaway as a brother, not a slave—the rest of the church is witness to Paul’s exhortation.

So the letter to Philemon has specific instructions for an individual church leader (like the pastoral epistles) but is addressed to a local congregation (like a church letter). You can learn more about Philemon’s role here.

Unlike the Gospels and Acts, the Pauline epistles hardly contain any narrative. These are primarily correspondence: Paul sends greetings, instructions, encouragement, and background information.

Because of this, the epistles contain the majority of Christians’ theology. This is where the story of Jesus described in the Gospels is explained in greater detail. It’s also where we learn how Christians should live in response to Christ’s life, death, and resurrection.

* Sometimes I’ll partner with organizations to help more people know about their resources—in return, they give me a kickback when people purchase. This is one of those times. ;-)